The Power of Poultry

- Case Studies, Featured

- Animals Systems, demonstration case study, Soil Health

We rotationally grazed poultry for meat production using a poultry tractor on depleted soil to demonstrate a low-staff-hours management system and to observe soil and grass health while considering economic viability for regional farmers.

Date of work: 2025

Farm Staff: Abby DeVries, gg glasson, Megan Beale

Pasture Consultant: Sarah Flack, Author of The Art and Science of Grazing

Location: Newport, RI, USA

Climate: Classification: Temperate oceanic

Growing Zone: USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 7a

Parent Soil Type: Canton and Charlton fine sandy loams; well-drained and include up to 20% rock formation. The soil is extremely acidic in wet areas, but otherwise is moderately acidic.

At Ocean Hour Farm, like many farmers in the Northeastern United States, we face soils depleted of nutrients. This can happen from growing annual crops in the same place for a long time or, as in our case, when attempting to transition from a grass field to a productive pasture. The lack of nutrients is commonly addressed through the use of fertilizers, synthetic or organic, to replenish the three essential nutrients in farming: NPK, which stands for Nitrogen (N), Phosphorus (P), and Potassium (K). Other key nutrients that are often depleted are calcium, magnesium, and trace minerals such as boron, zinc, and copper. You can test the availability of these nutrients in the soil with chemical soil tests through the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

“The challenge your farm faces is that due to previous history on the farm, you have inherited soils which have been depleted of fertility, and have significant compaction, including soil surface compaction. Surface compaction is causing rainfall to run over and off the surface and even pool on some areas of the soils instead of infiltrating into the soils.” – Sarah Flack

As regenerative farmers, we wanted to use animals (and their poop) to replenish soil nutrients rather than conventional fertilizers. There is significant research on the benefits to soil when poultry are rotationally grazed in pastures, and we wanted to demonstrate how this could work on a small-scale farm in our region while identifying the challenges and lessons learned, so other farmers don’t have to make the same mistakes.

Poultry was also selected as it provides fast-acting ‘hot fertilizer.’ Their swift growth allowed us to plan for two rounds of pasture-raised chickens and one round of pasture-raised turkeys.

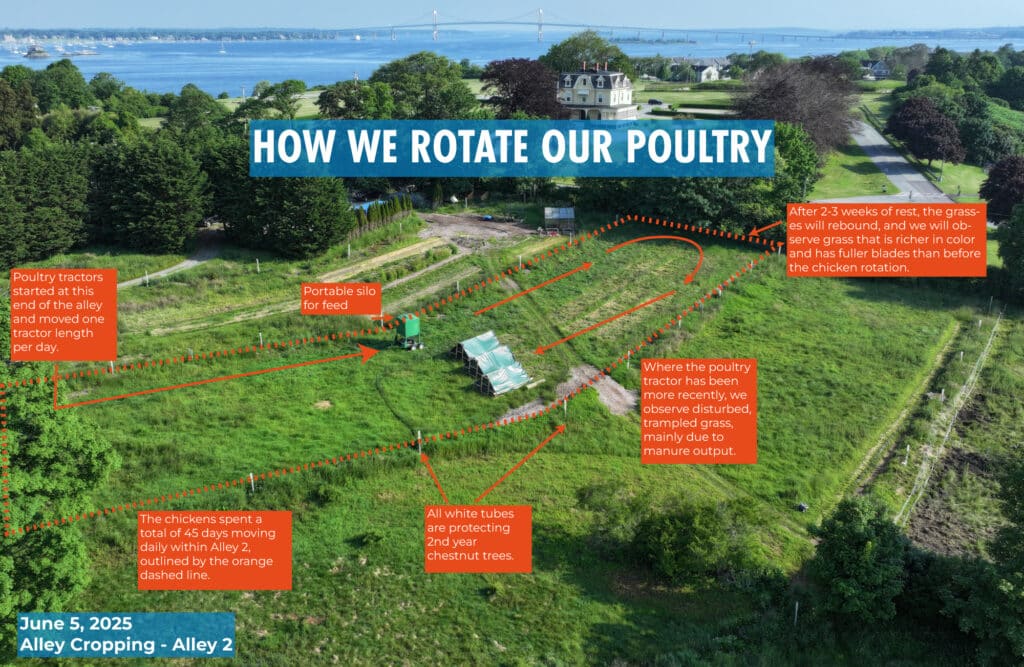

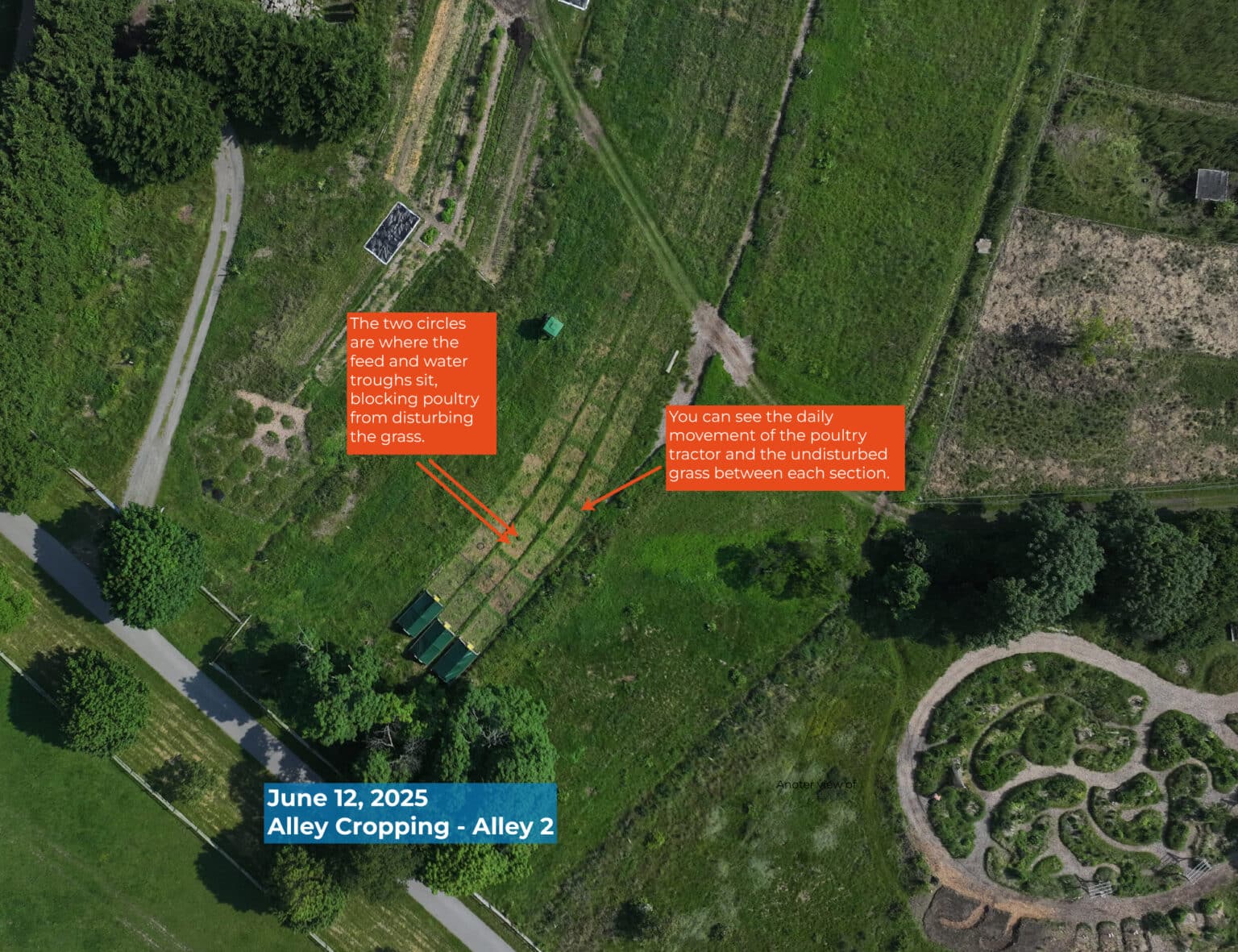

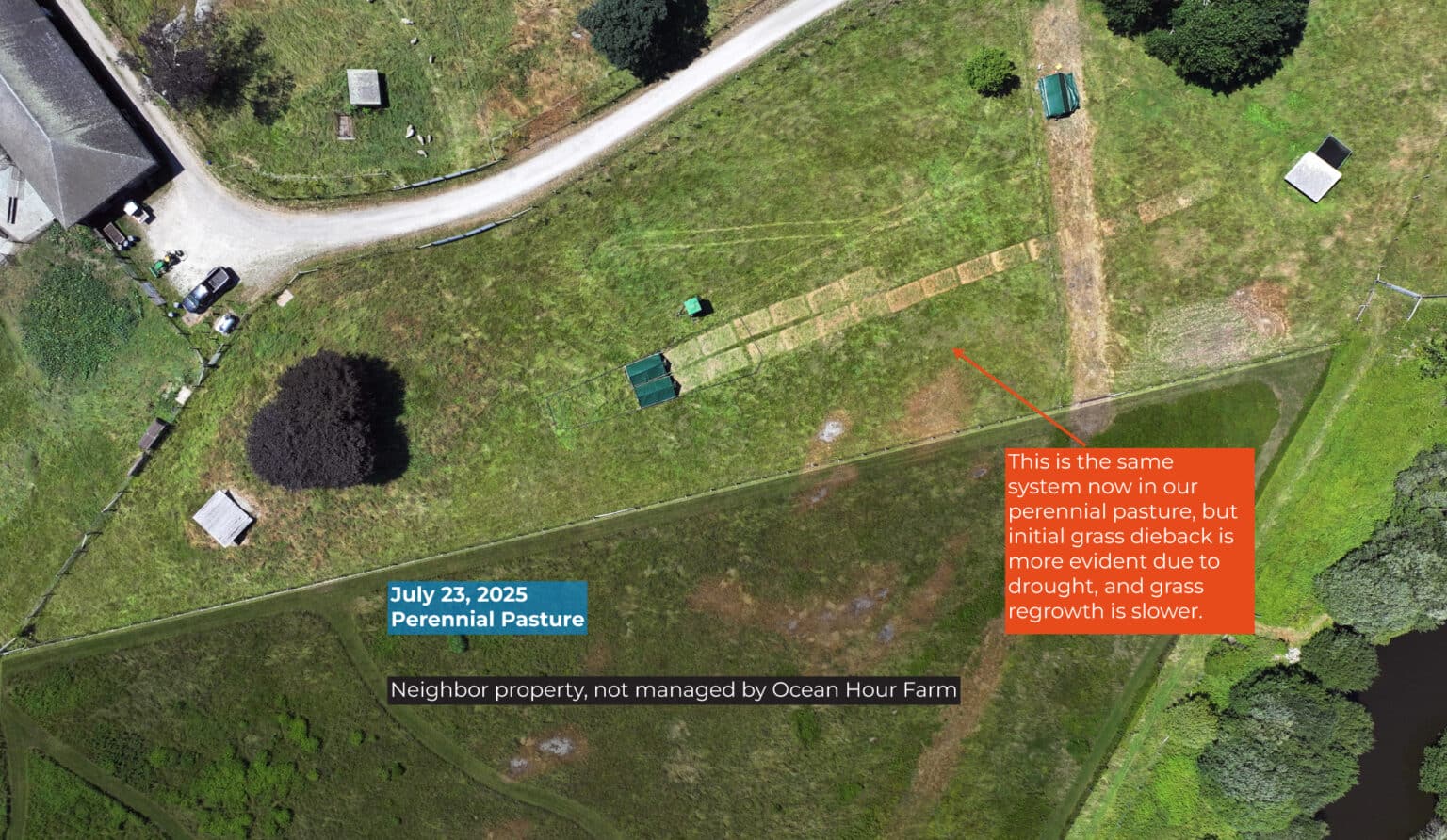

We rotated poultry in two locations, our alley cropping land unit and our perennial pasture, to improve soil health for grasses.

Poultry tractors rotate between two rows of chestnut trees. They are moved one tractor length per day. After 2-3 weeks of rest, the grasses rebound and come back more vibrantly. The chickens spent a total of 45 days in the area outlined by the orange dashed line.

We have a lot of previously used equipment and opted to repair and remake older equipment into the poultry tractors we desired. In the end, the biggest challenge our team faced was moving and repairing the poultry tractors. The older, heavy equipment was difficult to move on our sloped, rocky, and bumpy fields, and we imagine this would be the case for many New England Farmers. Additionally, the tractors’ weight required more staff time to move the poultry daily. Purchasing this wheel kit and mounting it on the rear of the coops alleviated some of these challenges. Had we started from scratch, we would have purchased these tractors, thereby significantly increasing startup costs.

We also encountered wildlife predation that could be financially devastating. In the final weeks of raising turkeys, we kept them outside the tractors but inside an electric-netted fence that our team had successfully used at other farms, but this time resulted in a significant loss.

As we have many other animal systems on site, we found that three staff members sharing the responsibility for this work was necessary.

We purchased 300 chicks and 42 turkeys, and raised 240 chickens and 15 turkeys to full size, yielding 1,378 pounds of protein. We’ve done our best to document our expenses in the table below; however, we used a lot of on-site equipment rather than purchasing new.

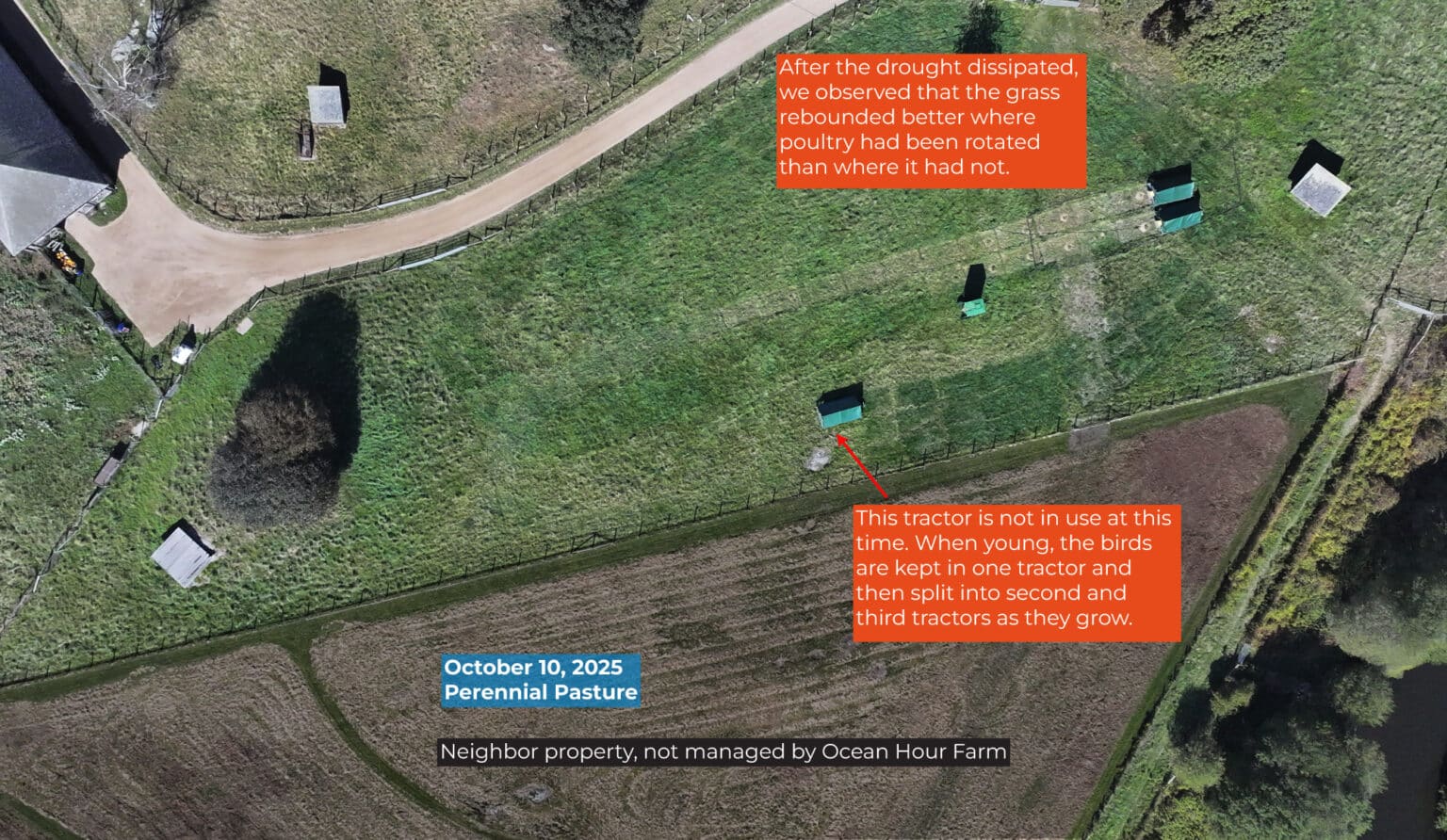

After the poultry had been rotated through a section and the grass had recovered, we observed that the grass was richer in color, had fuller blades, and had stronger, deeper roots than in areas where the chickens had not been present. Many factors could contribute to these changes, and we did not run a research trial to prove this due to the presence of the poultry, as this research has already been conducted by much larger organizations.

“The healthiest soils we saw were in areas where you had done some disturbance to the soil surface with pigs or chickens, or when moving some of the shade sheds and had added some seeds. Those areas had improved plant species, much better forage quality for livestock, but most importantly, those were the only areas where we saw new soil aggregation happening, less compaction, and water was able to soak into the soil surface.” – Sarah Flack, Author of The Art and Science of Grazing & Farm Consultant

Pictured left: This sample was dug up 10.5 weeks after the poultry had been active on the pasture. Sarah Flack, our pasture consultant, pictured here, noted several strong indicators of healthy soil. The first was good aggregate structure, which is how the soil particles stick to one another. The structure observed here is considered “crumb-like,” which promotes good aeration, water infiltration, and nutrient cycling.

Adding fertilizer, including chicken manure, to depleted soils can lead to excess runoff into our waterways, harming the health of both freshwater and saltwater ecosystems and creating oxygen-deprived dead zones. These issues are well-documented in the Chesapeake Bay.

However, in a rotational grazing system for poultry, the animals inherently fertilize more slowly than when fertilizer is applied broadly by humans or machines. Rotational grazing has been studied for many years and has proven to improve soil health, allowing the soil to absorb more water, reduce runoff, filter pollutants, and, therefore, enhance ocean health.

These studies show that livestock can be raised in ways that are detrimental or beneficial to the environment. As we increase livestock at Ocean Hour Farm, we continue to monitor water quality at seven on-site locations to detect any impact and follow regenerative methods proven to benefit the soil.

This case study demonstrates a regenerative farming technique; it is not a research trial. Our writing details how we implemented these concepts on our land and the field observations made by experienced farmers.

Our preparation work focused on restoring on-site mobile chicken coops and installing electric fences to protect against predators. Our goal was to have equipment that one person could move and to provide the poultry with sufficient room to grow. Our animal systems team focused on how to easily move water and feed around the field, aiming to keep daily chore time to 30 minutes.

Our plans called for three poultry tractors, as we would split the flock as the animals grew and needed more space. We had 3 movable coops with extendable fencing for extra protection for the broilers and to extend space for the turkeys.

We tested two different chicken breeds and brought in turkeys for the third round of field poultry testing. We timed the turkeys to coincide with the Thanksgiving holiday to align with economic viability and to demonstrate that the same equipment used for broilers works for turkeys.

We also selected Kosher Kings and Freedom Rangers instead of the more common Cornish Cross. The breeds we selected grow for a longer period and are generally healthier, but are not the most efficient birds from an economic perspective, as you feed them for roughly two more weeks.

For every pound of meat a bird gains, they are being fed an estimated four pounds of grain. By having breeds that need an additional 2 weeks of grain, we are spending more per bird, but ultimately meeting our goal of more nutrients in the soil.

| Date | Activity | Notes |

| Early April | 150 Freedom Rangers chicks arrive | Kept warm and safe inside with lights and pine shaving bedding |

| Late April | Pullets head to the field | Chicks started in one tractor and were separated into two tractors when overcrowding occurred, then into three tractors. |

| Early May | Flock is split into two tractors | Roughly 75 birds per tractor |

| Late May | Flock is split into three tractors | Approximately 40 to 50 birds per tractor |

| Early June | 150 kosher kings chicks arrive, second set of broilers | Kept warm and safe inside with lights and pine shaving bedding |

| July 1 | First set of freedom rangers chickens processed | Feed staff on-site and at home |

| July 2 | The second set of pullets, kosher kings, heads to the field | Kept in one tractor while small, and then split into second and third tractors as needed, moved every day, one length of the coop |

| Late August | 42 turkey chicks arrive | Kept warm and safe inside with lights and pine shaving bedding |

| Sept 2 | Second set of chickens, kosher kings, processed | Shared with the community at the Equinox dinner |

| Sept 3 | Turkeys in poultry tractors | Kept in one tractor while small, and then split into second as needed, moved every day, one length of the coop. |

| Nov 3 | Wildlife pressure resulted in a partial loss of the flock | The turkeys were raised in two poultry tractors, as the third was being repaired; they were therefore raised in and outside tractors with an electric fence, a common practice, but it did not work at our location. |

| Nov 17 | Turkeys processed | Given to staff for the holiday |

| Items | Costs |

| Pine shavings bedding for chicks (yearly cost) | $77.50 |

| Heat Lamps (one-time cost) | $32 for 2 |

| Brooder Boxes (one-time cost) | $160 for 2 |

| Poultry Tractor (one-time cost)

*We opted to repair old equipment; the cost listed is the price of tractors we would have purchased. |

$11,262 for 3 |

| Water Bells (one-time cost)

*We purchased much of our equipment used from a local farm no longer working with poultry, but we have provided links to similar equipment. |

$228 for 3 |

| Hanging Feeder (one-time cost) | $129 for 3 |

| Electric Poultry Net (one-time cost) | $642 for 3 nets |

| Chicks Supplies Pine shavings bedding for chicks (yearly cost) |

$77.50 |

| Poultry (yearly cost)

150 Freedom Ranger ($1.55 each) (males & straight run for orders of 100-499) 150 Kosher Kings ($1.55 each) (males & straight run for orders of 100-499) 42 Bronze Turkeys ($10.50 each) (orders of 41-80) Sent in three separate shipments |

$1,183 |

Feed (yearly cost)

|

$4,864.46 |

| Bulk Feed Bin (one-time cost) | $3,500 |

| Processing (yearly cost) | $2,815.35 |

| Estimated Labor (annual cost, details of how staff used time below) | 117.5 hours |

| Estimated Gross Revenue

This estimated cost per pound targets the middle ground between wholesale and retail, excluding all marketing and sales overhead. |

|

| 1,195 lbs of Chicken @ $9 per pound | $10,755 |

| 183 lbs of Turkey @ $12 per pound | $2,196 |

Estimated Labor

Our team was encouraged by the changes they observed in grass quality and enjoyed raising the poultry in the pasture. Future concepts they will look into include: